December 17, 2024

4 min read

Book Review: This Relationship Shaped Rachel Carson’s Environmental Ethos

The connection between queer love and the power to imagine a more sustainable future

NONFICTION

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love

by Lida Maxwell.

Stanford University Press, 2025 ($25)

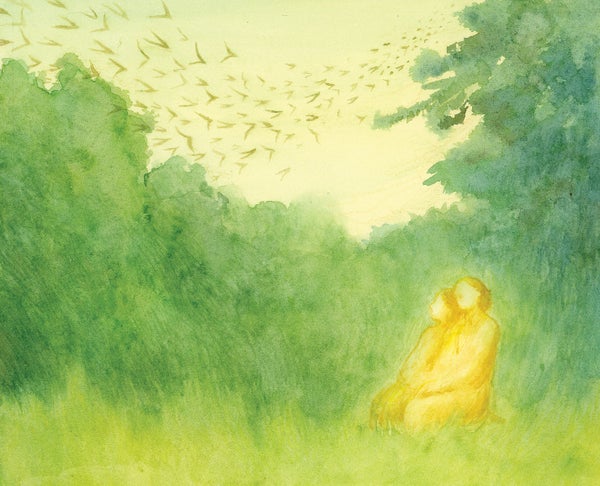

On a summer night in the mid-1950s, two women lay side by side on Dogfish Head, a spit of land on Maine’s jagged coast where a river meets the ocean. They took in the dazzling stars, the smudged filaments of the Milky Way, the occasional flash of a meteor. One woman was Rachel Carson, who would become well known for her book Silent Spring and its galvanization of the modern environmental movement; the other, Dorothy Freeman, was Carson’s married neighbor. The two had been drawn together from the moment they met in 1953 on Southport Island, Maine, and remained close until 1964, when Carson died of cancer. It was Freeman who scattered Carson’s ashes.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The scene on Dogfish Head may sound romantic, and Lida Maxwell’s new book, Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, argues that it indeed was. Maxwell, a professor of political science and of women, gender and sexuality studies at Boston University, explores the intimate bond between Carson and Freeman by drawing, in part, from a trove of personal letters. The book’s message is that the relationship holds a lesson for our modern climate crisis, especially for those of us willing to find meaning outside our culture’s dominant narratives.

The correspondence is telling. Carson professes strong feelings after just a few letters (“Because I love you! Now I could go on and tell you some of the reasons why I do, but that would take quite a while, and I think the simple fact covers everything …”). The two call each other “darling” and “sweetheart.” During the stretches they spend physically apart, they express what can easily be read as queer yearning, as when Freeman writes: “How I would love to curl up beside you on a sofa in the study with a fire to gaze into and just talk on and on.”

There is also reference to the hundreds of letters we’ll never read because the two women burned them, perhaps in that same fireplace. As Martha Freeman, Dorothy’s granddaughter, told Maxwell, “Rachel and Dorothy were initially cautious about the romantic tone and terminology of their correspondence.”

Was Carson a lesbian? The answer has long been the source of speculation. It’s impossible to know; she’s not known to have publicly identified as such. To Maxwell, though, this question is beside the point: “Whether or not their love was ‘homosexual,’ to use the language of the time, it was certainly queer. It drew them out of conventional forms of marriage and family and allowed them to find happiness where their society told them they weren’t supposed to: in loving each other and the world of nonhuman nature.”

Queer love is a rejection of what Maxwell calls “the ideology of straight love,” or the pursuit of “the good life” through marriage, buying and decorating a house, having and raising children, and participating in the treadmill of consumer culture to keep it all running. Because Carson and Freeman’s love was queer, Maxwell argues, they had no template with which to explore it. Instead they created a new language, expressed through a shared love of nature: the song of the veery, the Maine tide pools, the woods between their houses. This avenue for connection and meaning making, Maxwell argues, is what made Carson’s Silent Spring possible—it changed her from a writer who captured the wonder of nature to one advocating to save it.

How does this apply to the climate crisis? “As perhaps is obvious,” Maxwell writes, “the tight connection of the ideology of straight love with consumption is also bad for our climate because it ties our intimate happiness to unsustainable ways of living.” To truly achieve meaningful climate policy, she continues, we’ll need to expand our “visceral imaginary of what a good life could be.” The queer version embraces a “vibrant multispecies world” where we seek “desire and pleasure outside of the ideologies of capitalism and straight love.” These specific points, made throughout the book, are at times repetitive and can feel didactic.

Some readers, particularly straight readers, may bristle at all this. After all, plenty of people who don’t identify as queer opt out of consumerism and fight climate change. Straight people can reject the heteronormative story; queer people are not immune to it. But the point of the book isn’t that we should take individual action—it’s about broader structures and narratives. As a queer woman who spent a decade in a heteronormative marriage, I know how seductive the call of that particular “good life” can be; I also know the liberation of building something new. Max well’s book holds lessons for all readers about acknowledging, and then escaping, the structures that ensnare us.

Carson and Freeman found the way through their decidedly queer, deeply romantic, long-lasting love. Even when they were apart, they imagined themselves together. As Freeman writes during one of these spells: “You and I have been walking on the Head in the moonlight. Do you remember the night we lay there in that lovely light? I told you you looked like alabaster. You did. How happy we were then.”