November 19, 2024

3 min read

December 2024: Science History from 50, 100 and 150 Years Ago

Alcohol in space; basking in the limelight

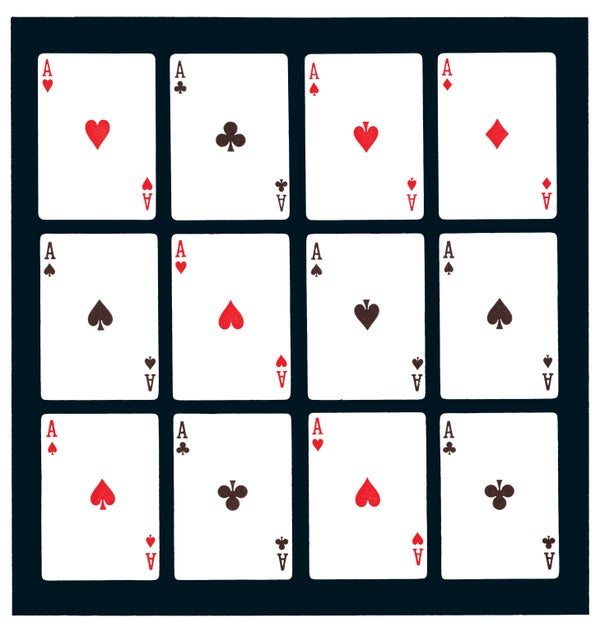

1974, How Many Aces of Spades?: “After a brief glance at this display most people report seeing three. Actually there are five. Because people expect aces of spades to be black, they tend to miss the atypical red ones. Thus do prior conditioning and experience influence perception.”

Scientific American, Vol. 231, No. 6; December 1974

1974

More Alcohol Found in Space

“Is there intelligent life elsewhere in the universe? Positive evidence facetiously adduced was that whereas methyl alcohol had been discovered in interstellar space, ethyl alcohol (the potable kind) had not. Clearly someone had consumed the stuff. But in October a group of [researchers] used a highly sensitive spectrometer to investigate the dense cloud of gas and dust designated Sagittarius B2, a rich source of most of the known molecules in space. They discovered weak radio emission at the wavelength of 3.3 millimeters [and] identified it as radiation from ethyl alcohol. Ethyl alcohol, composed of nine atoms (C2H5OH), is one of the largest and most complex molecules now known to exist in interstellar space. The substance is spread in a thin vapor throughout Sagittarius B2, which is some 50 light-years in diameter. One calculation shows that, if the ethyl alcohol were condensed, it would come to 1028 fifths of a gallon at 80 proof. Potability, however, might be a problem; the alcohol is heavily contaminated with substances such as hydrogen cyanide, formaldehyde and ammonia. The discovery brings the total number of different kinds of molecules detected in space to 32.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

1924

“Methanol” Is a Safer Name

“Some time ago attention was called to the coinage of this word to designate methyl alcohol, commonly called wood alcohol. The purpose was to provide a trade designation which would not involve the word ‘alcohol’ and consequently detract from the use of this material as a beverage. In one year in one of our larger cities there were 54 deaths traceable to the internal use of wood alcohol. As soon as the word ‘methanol’ had been accepted by the trade and users, the number of deaths in the same locality dropped to less than 20 in a year. It is believed that a great deal more has been accomplished by this ingenious device than would have been possible by any campaign of education or legal enforcements.”

Chromosomes, Not Jelly

“With the microscopic study of the cell and its constituent parts, and the rediscovery of Mendel’s law in 1900, two formerly independent lines of investigation have reinforced each other. We now know that living cells are not mere drops of jelly; each contains a complexity of parts, one of which is the easily dyed speck called the nucleus. The nucleus in turn contains a number of highly important microscopic constituents called chromosomes, of which each species of plant or animal possesses a characteristic number. Although the nature and behavior of these little chromosome particles are not fully understood, it is quite evident that they have very much if not everything to do with determining the great facts of heredity.”

1874

Paintings Bask in the Limelight

“The new and celebrated painting ‘Roll Call’ [by Lady Elizabeth Butler] is now nightly exhibited in London to large audiences, by means of the oxyhydrogen light, or lime light, and all the colors of the picture are brought out with marvelous brilliancy, in fact with the same perfection as by daylight. The idea of illuminating art galleries in the evening by the lime light is an excellent one. The yellow color of the ordinary gas flame reveals only a portion of the colors of the paintings. The reds and yellows are seen well enough, but the blues and greens, and their various tints, are sadly distorted, and the artistic effect lost. Lime light obviates such difficulties.”

Levett Ibbetson is credited with pioneering the use of limelight in photography. An oxyhydrogen flame (a mixture of oxygen and hydrogen) heated a piece of quicklime until it became white-hot, creating incandescence.

Sanitary Hospital Walls

“A writer in the London Builder suggests that thick glass might be easily and cheaply cemented to the walls of hospitals. It would be non-absorbent, imperishable, easily cleaned, readily repaired if damaged by accident, and unlike paper and paint, would always be as good as at first. Glass can be cut or bent to any required shape. If desired, the plates may be colored any cheerful tint. The non-absorbent quality is the most important for hospitals and prisons, and, we should think, is worthy the consideration of architects.”