Getty Images

Getty ImagesEarly on Friday morning, a 31-year-old female trainee doctor retired to sleep in a seminar hall after a gruelling day at one of India’s oldest hospitals.

It was the last time she was seen alive.

The next morning, her colleagues discovered her half-naked body on the podium, bearing extensive injuries. Police later arrested a hospital volunteer worker in connection with what they say is a case of rape and murder at Kolkata’s 138-year-old RG Kar Medical College.

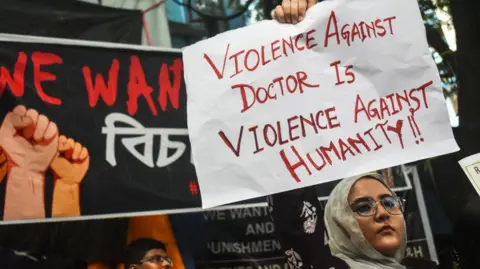

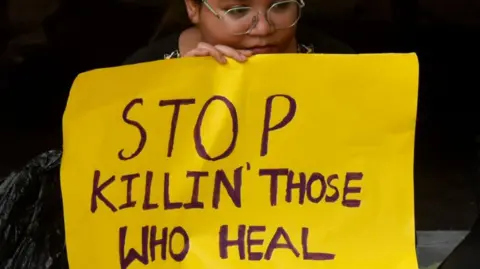

Enraged doctors went on strike both in the city and across India, demanding a strict federal law to protect healthcare workers. The tragic incident has again cast a spotlight on the violence against healthcare workers in the country.

Women make up nearly 30% of India’s doctors and 80% of the nursing staff. They are also more vulnerable than their male colleagues. Official data reveals a troubling 4% increase in crimes against women in 2022, with over 20% of these incidents involving rape and assault.

The crime in the Kolkata hospital last week exposed the alarming security risks faced by them in many of India’s state-run health facilities.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt RG Kar Hospital, which sees over 3,500 patients daily, the overworked trainee doctors – some working up to 36 hours straight – had no designated rest rooms, forcing them to seek rest in a third-floor seminar room.

Reports indicate that the arrested suspect, a patient volunteer with a troubled past, had unrestricted access to the ward and was captured on CCTV. Police allege that no background checks were conducted on the volunteer.

“The hospital has always been our first home; we only go home to rest. We never imagined it could be this unsafe. Now, after this incident, we’re terrified,” says Madhuparna Nandi, a junior doctor at Kolkata’s 76-year-old National Medical College.

Dr Nandi’s own journey highlights how female doctors in India’s government hospitals have become resigned to working in conditions that compromise their security.

At her hospital, where she is a resident in gynaecology and obstetrics, there are no designated rest rooms and separate toilets for female doctors.

“I use the patients’ or the nurses’ toilets if they allow me. When I work late, I sometimes sleep in an empty patient bed in the ward or in a cramped waiting room with a bed and basin,” Dr Nandi told me.

She says she feels insecure even in the room where she rests after 24-hour shifts that start with outpatient duty and continue through ward rounds and maternity rooms.

One night in 2021, during the peak of the Covid pandemic, some men barged into her room and woke her by touching her, demanding, “Get up, get up. See our patient.”

“I was completely shaken by the incident. But we never imagined it would come to a point where a doctor could be raped and murdered in the hospital,” Dr Nandi says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat happened on Friday was not an isolated incident. The most shocking case remains that of Aruna Shanbaug, a nurse at a prominent Mumbai hospital, who was left in a persistent vegetative state after being raped and strangled by a ward attendant in 1973. She died in 2015, after 42 years of severe brain damage and paralysis. More recently, in Kerala, Vandana Das, a 23-year-old medical intern, was fatally stabbed with surgical scissors by a drunken patient last year.

In overcrowded government hospitals with unrestricted access, doctors often face mob fury from patients’ relatives after a death or over demands for immediate treatment. Kamna Kakkar, an anaesthetist, remembers a harrowing incident during a night shift in an intensive care unit (ICU) during the pandemic in 2021 at her hospital in Haryana in northern India.

“I was the lone doctor in the ICU when three men, flaunting a politician’s name, forced their way in, demanding a much in-demand controlled drug. I gave in to protect myself, knowing the safety of my patients was at stake,” Dr Kakkar told me.

Namrata Mitra, a Kolkata-based pathologist who studied at the RG Kar Medical College, says her doctor father would often accompany her to work because she felt unsafe.

Getty Images

Getty Images“During my on-call duty, I took my father with me. Everyone laughed, but I had to sleep in a room tucked away in a long, dark corridor with a locked iron gate that only the nurse could open if a patient arrived,” Dr Mitra wrote in a Facebook post over the weekend.

“I’m not ashamed to admit I was scared. What if someone from the ward – an attendant, or even a patient – tried something? I took advantage of the fact that my father was a doctor, but not everyone has that privilege.”

When she was working in a public health centre in a district in West Bengal, Dr Mitra spent nights in a dilapidated one-storey building that served as the doctor’s hostel.

“From dusk, a group of boys would gather around the house, making lewd comments as we went in and out for emergencies. They would ask us to check their blood pressure as an excuse to touch us and they would peek through the broken bathroom windows,” she wrote.

Years later, during an emergency shift at a government hospital, “a group of drunk men passed by me, creating a ruckus, and one of them even groped me”, Dr Mitra said. “When I tried to complain, I found the police officers dozing off with their guns in hand.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThings have worsened over the years, says Saraswati Datta Bodhak, a pharmacologist at a government hospital in West Bengal’s Bankura district. “Both my daughters are young doctors and they tell me that hospital campuses are overrun by anti-social elements, drunks and touts,” she says. Dr Bodhak recalls seeing a man with a gun roaming around a top government hospital in Kolkata during a visit.

India lacks a stringent federal law to protect healthcare workers. Although 25 states have some laws to prevent violence against them, convictions are “almost non-existent”, RV Asokan, president of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), an organisation of doctors, told me. “Security in hospitals is almost absent,” he says. “One reason is that nobody thinks of hospitals as conflict zones.”

Some states like Haryana have deployed private bouncers to strengthen security at government hospitals. In 2022, the federal government asked the states to deploy trained security forces for sensitive hospitals, install CCTV cameras, set up quick reaction teams, restrict entry to “undesirable individuals” and file complaints against offenders. Nothing much has happened, clearly.

Even the protesting doctors don’t seem to be very hopeful. “Nothing will change… The expectation will be that doctors should work round the clock and endure abuse as a norm,” says Dr Mitra. It is a disheartening thought.