As a graphics editor at Scientific American, I spend a lot of time thinking about and visualizing data—including data on medical risks. So when I got pregnant in 2018, I was prepared for things to be complicated. Some of the most common issues loomed in my mind: for example, as many as one in five known pregnancies ends in miscarriage, and an estimated 13 percent of expectant people develop potentially dangerous blood pressure disorders. When no such problems arose in my pregnancy, I exhaled and concluded that I was lucky. I didn’t consider the sorts of diagnoses or events that affected less than, say, 1 percent of pregnancies. Those conditions, I reasoned, were rare.

How people think about rare events—especially unwelcome ones such as traumatic medical episodes or distressing diagnoses—seems to vary considerably depending on whether they have been directly affected by one. From my perspective one important implication of this phenomenon is that people mentally reframe the term “rare” as it applies in their own life. When a person is told that a particular bad outcome is extremely unlikely and then it happens anyway, they can understandably lose their trust in statistics as a reliable guide for decision-making, the consequences of which can be harmful.

At around eight months of pregnancy, I complained to my midwife of some itchy skin rashes that had popped up recently. She assured me that it was probably nothing to worry about but recommended a blood test to check for cholestasis. I had come across the term in my “pregnant and itchy” Google searches, so I knew that intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) was a liver condition that can develop in the third trimester and that it came with major risks for the fetus, including stillbirth. And I understood that the treatment was basically to get the baby out as soon as possible. But my symptoms didn’t quite line up with the most common presentations of ICP. Plus, the Internet told me, the condition affects only about one in 1,000 pregnant people in the U.S. It didn’t feel remotely likely that I would be that one.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A few days later I got an urgent phone call. You see where this is going: my cholestasis test had come back positive, and my midwife was advising me to go to the hospital that evening to be induced. Again my data-oriented brain kicked in. What, exactly, was the stillbirth risk if I were to carry to term? About 3 percent, she told me. Well, after apparently defying one-in-a-thousand odds, three-in-a-hundred sounded alarmingly probable. My hands shook as I called my husband. “It looks like we’re going to have a baby sooner than we thought,” I told him.

In many ways, a person’s belief that the unlikely can happen to them is potentially beneficial. Take, for example, the risk of death from skin cancer (a fate affecting 0.002 percent of the U.S. population). A person who takes that risk seriously might elect to wear sunscreen daily—a healthy choice with virtually no downside. As for my own decision to have labor induced to minimize risks to my child, the outcome included an emergency cesarean section, a procedure that comes with major risks and which may have been unnecessary had I waited for labor to begin spontaneously. (Luckily, the surgery went smoothly, and I was left with a healthy kid and no regrets.)

In certain cases, though, overestimating the risk of unlikely consequences can complicate what should be relatively straightforward health-related decisions. Imagine someone weighing whether to receive a routine vaccination that comes with a risk of side effects that are serious but vanishingly rare. If this person has been once bitten by a purportedly one-in-a-million sort of event, they might be twice shy when faced with another risk whose likelihood is characterized in a similar way. But, by refusing vaccination, they risk the far more plausible outcome of catching a preventable infection and spreading it to vulnerable members of their community.

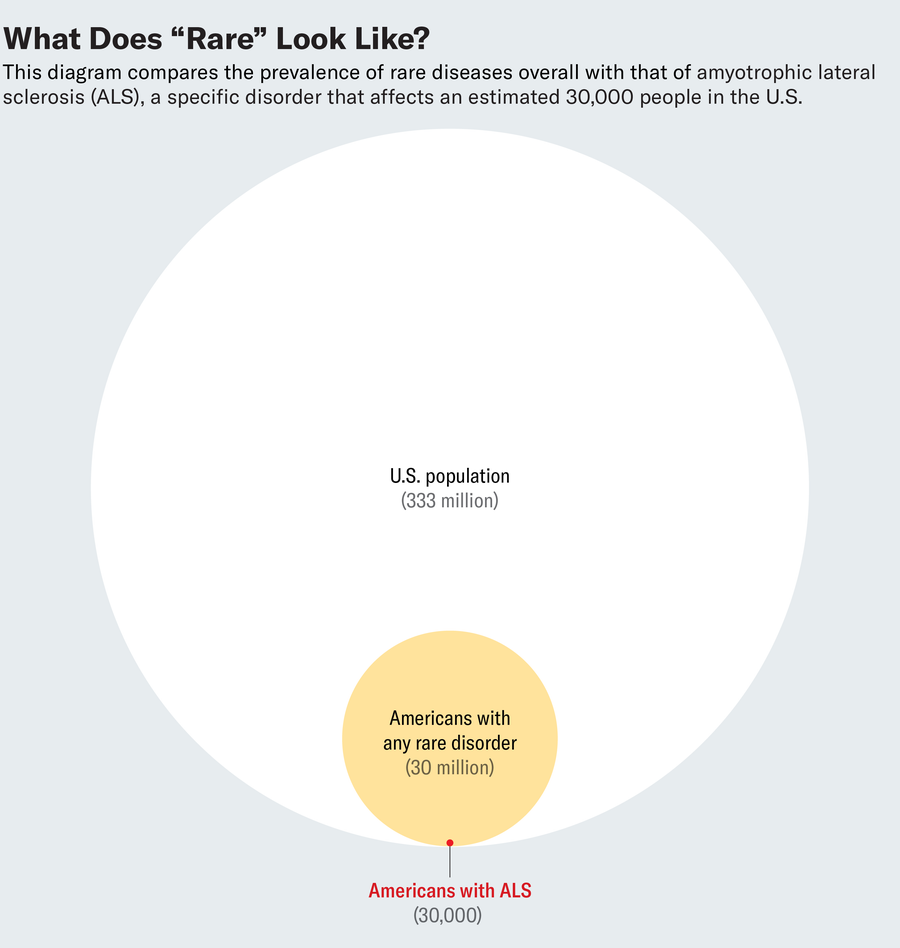

To combat the negative effects of this brand of risk aversion, it seems important to increase awareness of a few key concepts. First, there is a crucial difference between the probability of experiencing any unusual medical diagnosis and that of suffering a specific one. The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) defines a rare disease as one affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S., which works out to less than 1 percent of the population. But all 10,000 or so rare diseases collectively affect more than 30 million people in the U.S. That’s about one in 10 Americans. Rare diseases as a group, it turns out, are not rare at all.

Extending this principle to more self-contained medical events such as unusual side effects, it’s harder to cite specific data because the category is so broad. But given how long the average person lives and how frequently they make health choices that carry some risk, not only is it unsurprising that someone might experience something rare—it would be more remarkable if they never did.

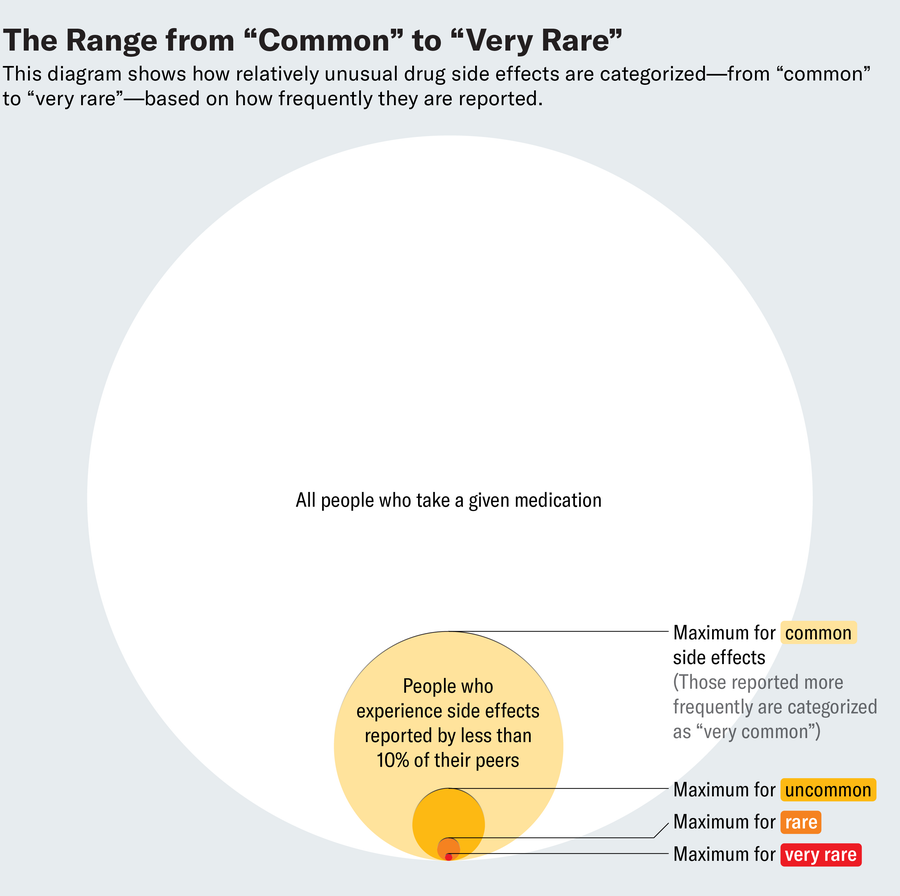

Second, terminology is critical. Colloquially, the expressions “uncommon,” “rare” and “very rare” don’t feel that different. But technically, they can differ by multiple orders of magnitude. In the context of drug side effects, those terms cover a range of statistical odds from up to one in 100 people to fewer than one in 10,000.

Adding to the complexity of risk assessment, medical risks can vary widely among different populations. Overall, women have a 13 percent chance of developing breast cancer in their lifetime. But for those with certain mutations in the genes known as BRCA1 or BRCA2, the risk exceeds 60 percent. As a result, members of the latter group might consider a prophylactic mastectomy, whereas for others, the benefits of surgery are unlikely to outweigh the drawbacks. Of course, there are many more cases where individual risk level is harder to calculate. But it can still be worthwhile to engage with what is known and try to estimate where one might fall within a range. (To wit, I might have been more prepared for my positive ICP test had I read a little further: prevalence among Latina women is estimated at about 6 percent).

Statistics aside, people are notoriously irrational in how they evaluate risks. We are more averse to the negative effects of our own choices if they result from action rather than inaction. (That’s why the prospect of getting a flu shot and suffering debilitating side effects can overshadow that of catching the flu after skipping the vaccine, even though the latter is far more likely to occur.) And we are often more easily swayed by emotions—rooted either in our own experiences or in poignant stories from others in our lives—rather than numbers. So ultimately, the remedy for this problem goes beyond pedantic lessons in medical risk data. It requires us to engage critically with our own human biases and, when necessary, push past them to make wise choices for ourselves and our communities.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.