August 20, 2024

4 min read

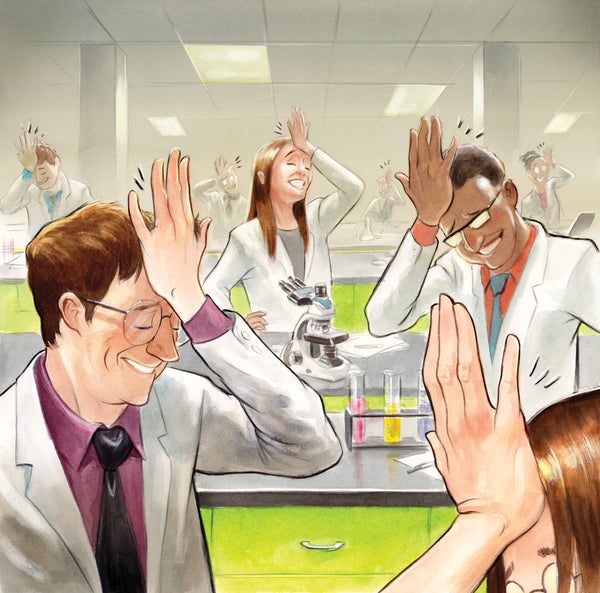

Science Improves When People Realize They Were Wrong

Science means being able to change your mind in light of new evidence

Many traits that are expected of scientists—dispassion, detachment, prodigious attention to detail, putting caveats on everything, and always burying the lede—are less helpful in day-to-day life. The contrast between scientific and everyday conversation, for example, is one reason that so much scientific communication fails to hit the mark with broader audiences. (One observer put it bluntly: “Scientific writing is all too often … bad writing.”) One aspect of science, however, is a good model for our behavior, especially in times like these, when so many people seem to be sure that they are right and their opponents are wrong. It is the ability to say, “Wait—hold on. I might have been wrong.”

Not all scientists live up to this ideal, of course. But history offers admirable examples of scientists admitting they were wrong and changing their views in the face of new evidence and arguments. My favorite comes from the history of plate tectonics.

In the early 20th century German geophysicist and meteorologist Alfred Wegener proposed the theory of continental drift, suggesting that continents were not fixed on Earth’s surface but had migrated widely during the planet’s history. Wegener was not a crank: he was a prominent scientist who had made important contributions to meteorology and polar research. The idea that the now separate continents had once been somehow connected was supported by extensive evidence from stratigraphy and paleontology—evidence that had already inspired other theories of continental mobility. His proposal did not get ignored: it was discussed throughout Europe, North America, South Africa and Australia in the 1920s and early 1930s. But a majority of scientists rejected it, particularly in the U.S., where geologists objected to the form of the theory and geophysicists clung to a model of Earth that seemed to be incompatible with moving continents.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the late 1950s and 1960s the debate was reopened as new evidence flooded in, especially from the ocean floor. By the mid-1960s some leading scientists—including Patrick M. S. Blackett of Imperial College London, Harry Hammond Hess of Princeton University, John Tuzo Wilson of the University of Toronto and Edward Bullard of the University of Cambridge—endorsed the idea of continental motions. Between 1967 and 1968 this revival began to coalesce as the theory of plate tectonics.

Not, however, at what was then known as the Lamont Geological Laboratory, part of Columbia University. Under the direction of geophysicist Maurice Ewing, Lamont was one of the world’s most respected centers of marine geophysical research in the 1950s and 1960s. With financial and logistical support from the U.S. Navy, Lamont researchers amassed prodigious amounts of data on the heat flow, seismicity, bathymetry and structure of the seafloor. But Lamont under Ewing was a bastion of resistance to the new theory.

It’s not clear why Ewing so strongly opposed continental drift. It may be that having trained in electrical engineering, physics and math, he never really warmed to geological questions. The evidence suggests that Ewing never engaged with Wegener’s work. In a grant proposal written in 1947, Ewing even confused “Wegener” with “Wagner,” referring to the “Wagner hypothesis of continental drift.”

And Ewing was not alone at Lamont in his ignorance of debates in geology. One scientist recalled that in 1965 he personally “was only vaguely aware of the hypothesis” [of continental drift] and that colleagues at Lamont who were familiar with it were mostly “skeptical and dismissive.” Ewing was also known to be autocratic; one oceanographer called him the “oceanographic equivalent of General Patton.” It wasn’t an environment that encouraged dissent.

One scientist who did change his mind was Xavier Le Pichon. In the spring of 1966 Le Pichon had just defended his Ph.D. thesis, which denied the possibility of regional crustal mobility. After seeing some key data at Lamont—data that had been presented at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union just that week—he went home and asked his wife to pour him a drink, saying, “The conclusions of my thesis are wrong.”

Le Pichon had used heat-flow data to “prove” that Hess’s hypothesis of seafloor spreading—the idea that basaltic magma welled up from the mantle at the mid-oceanic ridges, creating pressure that split the ocean floor and drove the two halves apart—was incorrect. Now new geomagnetic data convinced him that the hypothesis was correct and that something was wrong with either the heat-flow data or his interpretation of them.

Le Pichon has described this event as “extremely painful,” explaining in an essay that “during a period of 24 hours, I had the impression that my whole world was crumbling. I tried desperately to reject this new evidence.” But then he did what all good scientists should do: he set aside his bruised ego (presumably after polishing off that drink) and got back to work. Within two years he had co-authored several key papers that helped to establish plate tectonics. By 1982 he was one of the world’s most cited scientists—one of only two geophysicists to earn that distinction.

In the years that followed, Lamont scientists made many crucial contributions to plate tectonics, and Le Pichon became one of the leading earth scientists of his generation, garnering numerous awards, distinctions and medals, including (ironically) the Maurice Ewing Medal from the American Geophysical Union. In science, as in life, it pays to be able to admit when you are wrong and change your mind.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.