Getty Images

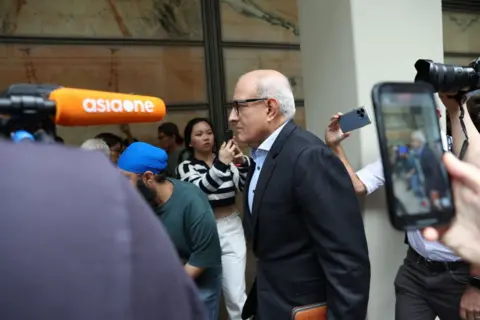

Getty ImagesSubramanian Iswaran, a senior cabinet minister in Singapore’s government, has been sentenced to 12 months in prison in a high-profile trial that has gripped the wealthy nation.

Iswaran, 62, pleaded guilty to accepting gifts worth more than S$403,000 ($311,882; £234,586) while in public office, as well as obstructing the course of justice.

The gifts included tickets to the Formula 1 Grand Prix, a Brompton T-line bicycle, alcohol and a ride on a private jet.

Justice Vincent Hoong, who oversaw the case in Singapore’s High Court, noted that the former transport minister seemed to think he would be acquitted.

“In his letter to the prime minister, he stated he rejected (the charges) and expressed his strong belief he would be acquitted,” said Justice Hoong.

“Thus I have difficulty accepting these are indicative of his remorse.”

It was not immediately clear when Iswaran would report to prison, but his lawyers asked the judge to expedite the process.

He will serve his sentence at Changi, the same prison that holds Singapore’s death row prisoners, where the cells don’t have fans and most inmates sleep on straw mats instead of beds.

He is Singapore’s first political figure to be tried in court in nearly fifty years.

The nation prides itself on its squeaky clean image and lack of corruption. But that image, and the reputation of the governing People’s Action Party, have taken a hit as a result of Iswaran’s case.

The city state’s lawmakers are among the highest-paid in the world, with some ministers earning more than S$1 million ($758,000). Leaders justify the handsome salaries by saying it combats corruption.

Ministers cannot keep gifts unless they pay the market value of the gift to the government, and they must declare anything they receive from people they have business dealings with.

“It’s not a significant sum over his years of service, but on his salary, he could have very well afforded not to,” said Eugene Tan, an associate professor of law at Singapore Management University.

“I think the public were expecting the court to demonstrate zero tolerance for this sort of conduct.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIswaran’s defence team had asked for eight weeks, if the judge deemed prison necessary. His lawyer argued the charges were not an abuse of power and did not disadvantage the government.

Prosecutors meanwhile requested an eight to nine-month sentence, saying Iswaran was “more than a passive acceptor of gifts”.

“If public servants could accept substantial gifts in such a situation, over the long term, public confidence in the impartiality and integrity of government would be severely undermined,” said Deputy Attorney-General Tai Wei Shyong.

“Not punishing such acts would send a signal that such acts are tolerated.”

While in government, Iswaran held multiple portfolios in the prime minister’s office: in home affairs, communications and, most recently, the transport ministry.

Prior to last year, the most recent case of a politician facing a major corruption probe was in 1986, when national development minister Teh Cheang Wan was investigated for accepting bribes. He took his own life before he was charged.

Before that, former minister of state for environment Wee Toon Boon was sentenced to 18 months jail in 1975 for a case involving more than $800,000.

Allegations against Iswaran first surfaced in July of last year. Nearly all the charges against him stem from his dealings involving billionaire property tycoon Ong Beng Seng, who helped bring the Formula 1 Grand Prix to Singapore. Ong Beng Seng is also under investigation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Iswaran discovered authorities were investigating Mr Ong’s associates he requested that Mr Ong bill him for his flight to Doha, Justice Hoong said on Thursday.

He acted with deliberation and premeditation, and in asking to be billed and paying for the ticket was trying to avoid investigations into the gifts, the judge added.

Iswaran was originally charged with 35 counts, including two counts of corruption, one charge of obstructing justice and 32 counts of “obtaining, as a public servant, valuable things”. But at a trial in late September, Iswaran pleaded guilty to lesser offences after the corruption charges were amended.

Lawyers did not confirm whether a plea deal had been reached.

“The system still works and there is still that public commitment. But this particular case is certainly not going to win the party any favours,” Mr Tan said.

The case against Iswaran is one of a series of political scandals that has rocked the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has long touted its strong stance against corruption and amoral behaviour.

In 2023, a separate corruption probe into the real estate dealings of two other ministers eventually cleared them of impropriety, while the speaker of Parliament resigned because of an extramarital affair with another lawmaker.

The property scandal raised questions about the privileged positions that ministers have in Singapore at a time of rising living costs.

Singapore must hold a general election by November 2025. The PAP’s share of the popular vote declined in the most recent elections, and it is facing a challenge to its decades-long one party dominance from an increasingly influential opposition party.

The Workers’ Party won a total of 10 seats in parliament in the last election, but has also been rocked by scandal. Its leader, Pritam Singh, has been charged with lying under oath to a parliamentary committee. He has rejected the accusations.