Slime Mold Helps to Map the Universe’s Tendrils of Dark Matter

A single-celled organism’s pathfinding reveals connections in the universe’s vast “cosmic web”

Over billions of years gravity has pulled the universe’s matter into a chaotic netting of filaments, tendrils and voids known as the cosmic web. Galaxies are strewn along these strands like beads on a string, and New Mexico State University astronomer Farhanul Hasan and his colleagues wondered how environments created by the filaments affect galaxies’ evolution. “I like to call them galactic ecosystems,” he says.

To find out, the researchers needed to accurately map the cosmic web over time. But the mixture of gas, galaxies and dark matter that constitutes the web makes this task challenging, because although the stars in the galaxies are easy to see, the rest is not.

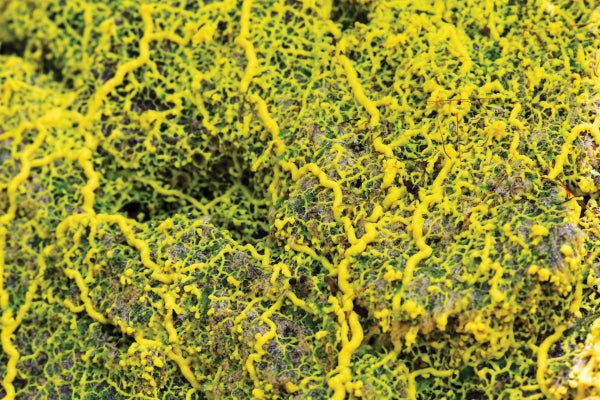

To connect the dots in a computer simulation of the universe, Hasan and his colleagues brought in a special “collaborator”: a species of the humble slime mold. These single-celled organisms are experts at exploring the space around them. Their membranes push outward in a synchronized wave in every direction. When they find a food source, nearby membranes relax, allowing subsequent pushes to send more material to that region.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Scientists have used slime molds’ exploration prowess to solve mazes and logic puzzles, to re-create transportation systems, and to inspire efficient computer algorithms. “It’s a really good mapping algorithm because it’s not really biased by the first direction you decide to look in; [it’s] capable of exploring everything at once,” says New Jersey Institute of Technology slime mold specialist Simon Garnier.

Hasan and his team gave a slime-mold-based algorithm a set of galaxies’ positions as “food” and let it map connections across the simulated universe at various time points. The slime-mold map created a cleaner filament structure than any human-designed algorithm they had tried; it was also sensitive to smaller features and traced dark matter more easily. The researchers found that neither the proximity nor the thickness of the universe’s filaments seemed to affect the galaxies early on, but as the universe matured, things changed: material pulled into the web eventually disrupted star formation in galaxies that were too close.

“The crucial difficulty in using the cosmic web to constrain galaxy formation is in describing it with the accuracy needed to observe its effect,” says New York City College of Technology astrophysicist Ari Maller. “The use of the slime-mold algorithm seems to have accomplished that goal.”

The study’s results, appearing in the Astrophysical Journal, are just the beginning. New surveys are stretching observations even further back in time. Conclusions from the simulated universe eventually can be tested against older glimpses of the real cosmic web—and the slime-mold algorithm is poised to map them all.