Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow will history judge my tenure?

That’s a question Dhananjay Yashwant Chandrachud, who retired as India’s 50th chief justice on Sunday, asked just weeks before he finished his term.

Justice Chandrachud said his mind was “heavily preoccupied with fears and anxieties about the future and the past”.

“I find myself pondering: Did I achieve everything I set out to do? How will history judge my tenure? Could I have done things differently? What legacy will I leave for future generations of judges and legal professionals?” he said.

The soul searching came at a time when many in India are also debating what legacy he leaves behind.

Justice Chandrachud served more than eight years as a top court judge and as chief justice for the past two years. He presided over one of the most powerful Supreme Courts in the world with jurisdiction over India’s 1.4 billion citizens.

The top court is the final court of appeal, the final interpreter of the constitution and its judgements, which are binding on all other courts in India, routinely make news – although judges seldom do.

But Justice Chandrachud, sometimes described as India’s “first celebrity judge” and a “rockstar judge”, has routinely hit the headlines.

PTI

PTIAccording to Arghya Sengupta of the Vidhi Centre For Legal Policy, the jurist was India’s most prolific chief justice who wrote 93 judgements – more than his last four predecessors put together – including some on matters of seminal importance. He also made huge strides in terms of digitisation and livestreaming of court hearings – making them more accessible to citizens.

But some of the recent coverage has also been unflattering, with critics saying he wasn’t assertive enough and his tenure has been disappointing.

The Harvard-educated judge has many firsts to his name – he was the youngest to head a high court and his two-year-term was the longest for a chief justice in more than a decade. He’s also the only chief justice whose father also served in the role.

During his years in the Supreme Court, he developed a reputation for being a progressive, liberal judge known for his nuanced and thoughtful judgements related to matters of liberty, freedom of speech and gender and LGBT rights.

He was part of landmark rulings that decriminalised homosexuality and allowed menstruating women into Kerala’s Sabarimala shrine. His utterances on the right to privacy and right to dissent were extensively praised.

So, his elevation to be India’s top judge in November 2022 was welcomed by senior lawyers, activists and citizens with many expressing a “strong hope that under his leadership the court will rise to greater heights”.

It was a time when India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government was getting ready to secure a third term in the 2024 general election.

Opposition parties, activists and sections of the press were accusing the government of targeting them, with global rights organisations saying Indian democracy was under threat.

Although the government denied any wrongdoing, many of India’s top academics, rights activists and popular opposition leaders found themselves in jail and the country kept sliding on the global press freedom index. (The government has always rejected such ratings, saying they are biased against India.)

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSenior lawyer Kamini Jaiswal says Justice Chandrachud’s appointment had come at “a crucial juncture as some of the last chief justices had left under a cloud of dark spots and the position had been denigrated with serious allegations”.

“So, we thought Justice Chandrachud would use his erudition and brilliant mind to do a lot of good for the citizens. But he has been disappointing,” she said.

Senior Supreme Court lawyer Chander Uday Singh says his record is “a mixed bag”.

“In his judgments, he would lay down the law brilliantly which could be used as a precedent for future cases. But whenever the state was heavily invested in any issue, he failed to hold power to account, so the state got away with what they had set out of achieve.”

For instance, he points out that the court struck down a government scheme that allowed people to make anonymous donations to political parties, calling it unconstitutional and illegal. “But then he did not hold anyone accountable for the illegality.”

Similarly, when it came to a political crisis in the western state of Maharashtra or Delhi’s power struggle with the federal government, his judgments tended to favour the government, he adds.

“There was hope that through his judgments, he would set things right in a country that is under a strong majoritarian government. But he fell short.”

EPA

EPASeveral top lawyers have also criticised Justice Chandrachud for what he did as the “master of the roster” by failing to effectively prevent the prolonged incarceration of political prisoners – leading to the death of some of them without ever getting bail. This happened despite Justice Chandrachud saying that bail should be the norm and not the exception.

And as he neared his retirement, Justice Chandrachud also made headlines for what he did not in the court, but outside.

In September, there was uproar over a viral video that showed him praying at home with PM Modi during a Hindu religious festival.

Ms Jaiswal said by publicising the photo, “a message was being sent that the chief justice is close to the PM”. Lawyers, former judges, opposition politicians and many citizens also criticised him saying “the presence of a politician at a private event erodes the perception of impartiality of the judiciary”.

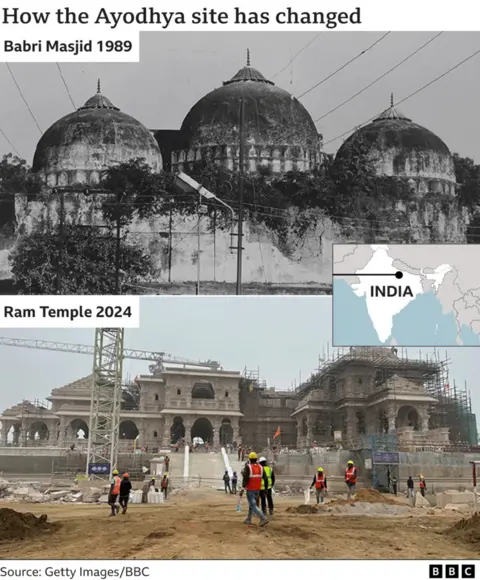

Another burst of criticism greeted Justice Chandrachud’s comment last month when he said he had asked God for a solution to the vexed Babri Mosque-Ram temple dispute. “I sat before the deity and told him he needed to find a solution and he gave it to me,” he said.

The comment led to a firestorm of criticism, not entirely unexpected as the mosque-temple dispute has been one of the most contentious and religiously polarising issues in modern India.

The mosque was demolished by Hindu mobs in 1992. A five-judge bench, which included Justice Chandrachud, ruled in 2019 that the demolition was illegal, but still gave the disputed land to Hindus and a separate site for the mosque to be built. Earlier this year, PM Modi inaugurated a grand new temple at the site, fulfilling a longstanding promise by his party.

So, no surprise then that Justice Chandrachud’s comment, seen by many as religious, was extensively criticised.

Retired high court judge Anjana Prakash told HW news that his comment was “dramatic, filmy and laughable and it had brought down the level of judiciary”.

“A judge has to decide cases on principles of law. Where does God come into a judgement? Besides, people have different gods. And if a justice from another faith had said this, would the reaction be the same?” she asked.

Justice Prakash and other critics wondered if he was cosying up to the government for a post-retirement assignment.

In the days preceding his retirement, Justice Chandrachud addressed some of the criticism in interactions with the media.

“The separation of powers doesn’t mean antagonistic relations between the executive and the judiciary, it doesn’t mean that they cannot meet,” he said at an event by the Indian Express newspaper, adding that such meetings were not used “to cut deals”.

“The ultimate proof of our good behaviour lies in the written word – in our judgements. Is it consistent with the constitution or not?”

Justice Chandrachud said his comment on seeking divine guidance was because “I am a person of faith” and “to impute motives to judges is not right”.

He added that courts were facing pressure “from lobbies and pressure groups” and they would praise a decision critical of the government, but if he ruled in favour of the government, they questioned his independence.

At his farewell on Friday, the outgoing chief justice said he was perhaps India’s most trolled judge, but his “shoulders are broad enough to accept all criticism”.

And at the weekend, he told Times of India that he believed he had “left the system better than I found it”.

“I’m retiring with a sense of satisfaction,” he said.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.