)

EV go fast-charging stations in Los Angeles | Photographer: Bing Guan/Bloomberg

For EV drivers traversing the great state of Wyoming, the Smith’s grocery store in Rock Springs is an oasis. It’s just off I-80, there’s a Petco across the street, and it has six plugs promising to charge at 350 kilowatts. At that rate, a Tesla Model 3 could go from empty to full in the time it takes to hit the bathroom and grab a Snickers.

But when I limped up to the station last month — in a Rivian R1S crammed with one dog and two kids — that 350 kW may as well have been a mirage. Rivian’s SUV charges at 220 kW at best, and the charger itself crimped the hose to just 50 kW. With one pit stop, our carefully planned seven-hour road trip got two hours longer.

This isn’t a Wyoming-specific problem, or a Rivian one. At US public stations promising charging speeds of 100 kW or higher, the average delivered charge was only 52 kW in 2022, according to Stable Auto, which helps networks decide where to build new infrastructure. That disconnect — largely a reflection of battery power’s idiosyncrasies — is leaving many US drivers guessing as to when, why and by how much their charge is being throttled.

There are many good reasons why even the slickest public chargers rarely run at maximum capacity. The chemical wizardry of battery power is more complex than pouring liquid in a tank, and both internal and external factors take a toll on charging speed.

)

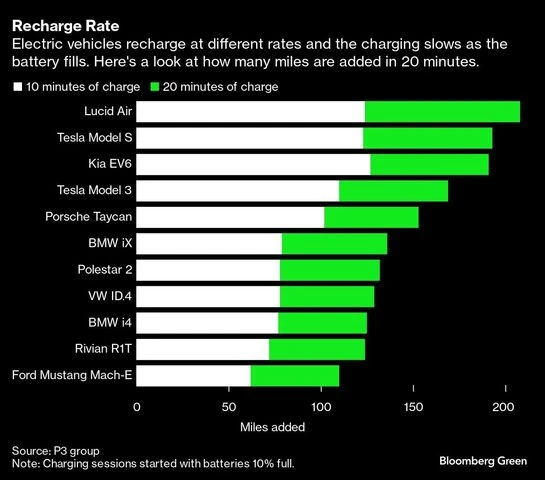

Trickier still, EV charging slows naturally as the car’s battery approaches full, in order to keep it from overheating. (Smartphones and laptops do the same thing.) The specifics of this charging curve are unique to each car, though brands are cagey about sharing those specifics, even with the people buying their products. Tesla vehicles, for one, have relatively steep charging curves, meaning the “fast” part of the charging doesn’t last long.

Finally, charging networks themselves crimp electron flow. On a hot day, the local grid might be maxed out by thirsty air conditioners, or the plugs’ hoses may be close to overheating. Many stations split power between cars, allowing them to install more cords with the same electricity. In other words, a 200 kW charger becomes a 100 kW charger when someone uses its second cord. (The US Department of Energy classifies plugs 50 kW and up as “fast.”)

“There’s sort of this complicated handshake between the vehicle and the charger, so I think there’s an education gap for sure,” says Sara Rafalson, executive director of policy at EVgo.

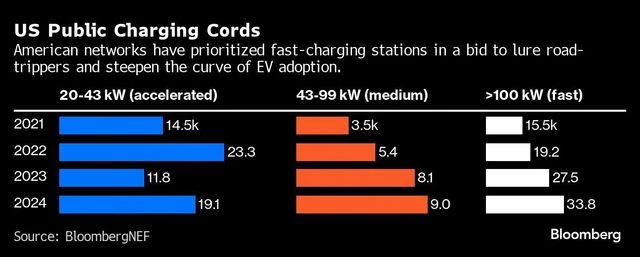

That gap risks hurting EV adoption in the US, where charging speed has become a marketing metric. Automakers like to trumpet how quickly their cars can go from 10 per cent or 20 per cent full to 80 per cent, while public charging stations tend to display maximum charge rate — not average or expected — right on the machines. Some 17 per cent of US public chargers are rated 100 kW-plus, according to BloombergNEF, compared with 10 per cent in the UK and 2 per cent in the Netherlands.

Consumers are a little less sanguine. One snapshot of 103,000 Tesla charging sessions found average charging speeds of 90 kW — less than half of the maximum, according to Recurrent Auto, a startup that tracks battery health. And in a recent JD Power survey, EV owners scored public charging speeds near the bottom of 10 categories studied. Brent Gruber, executive director of JD Power’s EV practice, says consumers develop false expectations “when you plaster those [kilowatt] numbers on the charger itself.”

)

Charging’s inherent complexity means the speed gap will never close entirely — but it should narrow in the near future. Charging networks are building faster and larger stations in the US, which will ease the need for power dilution across plugs. Since the end of 2022, every station built by Electrify America has been capable of 350 kW, and a couple of its sites now have 20 charging slots.

Carmakers have also realized that max charging rate is a deciding factor for car buyers, and are dialing it up on coming models. “There will be a catch-up on the technology side that should meet that catch-up on the learning-curve side,” Lambkin says.

But for the time being, the best way to cope with the unpredictability is to prepare for it — sometimes doggedly. Before Jacob Espinoza sets off on any road trip from his home in New Mexico, he goes through a three-part checklist: Plug his destination into a route-planning app; check the charging network apps; and check Plugshare, a platform for crowdsourced charger reviews.

“When you do those three things, it’s really not that hard to take long trips in an EV,” says Espinoza, who chronicles his battery-powered road trips on YouTube.

Back in Rock Springs, I was paying the price for having skipped Espinoza’s steps two and three. After about 15 minutes of 50 kW charging, we cut our losses and drove another 100 miles north to Pinedale, Wyoming, where two cords idled in a dusty lot behind Stockman’s Saloon and Steakhouse. The “Frontier Days” festival was in town, so we wandered by to catch a folk concert.

With a maximum charging speed of 120 kW, the Pinedale plug should have been far slower than our 350 kW machine in Rock Springs. But we only had 90 miles to go and it covered that in just a few minutes. Frontier days, indeed.

(Only the headline and picture of this report may have been reworked by the Business Standard staff; the rest of the content is auto-generated from a syndicated feed.)

First Published: Sep 05 2024 | 6:25 PM IST